Fizz Buzz with Cosines

Fizz Buzz is a counting game that has become oddly popular in the world of computer programming as a simple test of basic programming skills. The rules of the game are straightforward. Players say the numbers aloud in order beginning with one. Whenever a number is divisible by 3, they say 'Fizz' instead. If it is divisible by 5, they say 'Buzz'. If it is divisible by both 3 and 5, the player says both 'Fizz' and 'Buzz'. Here is a typical Python program that prints this sequence:

for n in range(1, 101):

if n % 15 == 0:

print('FizzBuzz')

elif n % 3 == 0:

print('Fizz')

elif n % 5 == 0:

print('Buzz')

else:

print(n)Here is the output: fizz-buzz.txt. Can we make the program more complicated? The words 'Fizz', 'Buzz' and 'FizzBuzz' repeat in a periodic manner throughout the sequence. What else is periodic? Trigonometric functions! Perhaps we can use trigonometric functions to encode all four rules of the sequence in a single closed-form expression. That is what we are going to explore in this article, for fun and no profit.

By the end, we will obtain a discrete Fourier series that can take any integer \( n \) and select the corresponding text to be printed. In fact, we will derive it using two different methods. First, we will follow a long-winded but hopefully enjoyable approach that relies on a basic understanding of complex exponentiation, geometric series and trigonometric functions. Then, we will obtain the same result through a direct application of the discrete Fourier transform.

Contents

Definitions

Before going any further, we establish a precise mathematical definition for the Fizz Buzz sequence. We begin by introducing a few functions that will help us define the Fizz Buzz sequence later.

Symbol Functions

We define a set of four functions \( \{ s_0, s_1, s_2, s_3 \} \) for integers \( n \) by: \begin{align*} s_0(n) &= n, \\ s_1(n) &= \mathtt{Fizz}, \\ s_2(n) &= \mathtt{Buzz}, \\ s_3(n) &= \mathtt{FizzBuzz}. \end{align*} We call these the symbol functions because they produce every term that appears in the Fizz Buzz sequence. The symbol function \( s_0 \) returns \( n \) itself. The functions \( s_1, \) \( s_2 \) and \( s_3 \) are constant functions that always return the literal words \( \mathtt{Fizz}, \) \( \mathtt{Buzz} \) and \( \mathtt{FizzBuzz} \) respectively, no matter what the value of \( n \) is.

Index Function

We define a function \( f(n) \) for integer \( n \) by \[ f(n) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } 3 \mid n \text{ and } 5 \nmid n, \\ 2 & \text{if } 3 \nmid n \text{ and } 5 \mid n, \\ 3 & \text{if } 3 \mid n \text{ and } 5 \mid n, \\ 0 & \text{otherwise}. \end{cases} \] The notation \( m \mid n \) means that the integer \( m \) divides the integer \( n, \) i.e. \( n \) is a multiple of \( m. \) Equivalently, there exists an integer \( c \) such that \( n = cm . \) Similarly, \( m \nmid n \) means that \( m \) does not divide \( n, \) i.e. \( n \) is not a multiple of \( m. \)

This function covers all four conditions involved in choosing the \( n \)th item of the Fizz Buzz sequence. As we will soon see, this function tells us which of the four symbol functions produces the \( n \)th item of the Fizz Buzz sequence. For this reason, we call \( f(n) \) the index function.

Fizz Buzz Sequence

We now define the Fizz Buzz sequence as the sequence \[ (s_{f(n)}(n))_{n = 1}^{\infty} \] We can expand the first few terms of the sequence explicitly as follows: \begin{align*} (s_{f(n)}(n))_{n = 1}^{\infty} &= (s_{f(1)}(1), \; s_{f(2)}(2), \; s_{f(3)}(3), \; s_{f(4)}(4), \; s_{f(5)}(5), \; s_{f(6)}(6), \; s_{f(7)}(7), \; \dots) \\ &= (s_0(1), \; s_0(2), \; s_1(3), \; s_0(4), s_2(5), \; s_1(6), \; s_0(7), \; \dots) \\ &= (1, \; 2, \; \mathtt{Fizz}, \; 4, \; \mathtt{Buzz}, \; \mathtt{Fizz}, \; 7, \; \dots). \end{align*} Note how the function \( f(n) \) produces an index \( i \) which we then use to select the symbol function \( s_i(n) \) to produce the \( n \)th term of the sequence. This is precisely why we decided to call \( f(n) \) the index function while defining it in the previous section.

From Indicator Functions to Cosines

Here we discuss the first method of deriving our closed form expression, starting with indicator functions and rewriting them using complex exponentials and cosines.

Indicator Functions

Here is the index function \( f(n) \) from the previous section with its cases and conditions rearranged to make it easier to spot interesting patterns: \[ f(n) = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{if } 5 \nmid n \text{ and } 3 \nmid n, \\ 1 & \text{if } 5 \nmid n \text{ and } 3 \mid n, \\ 2 & \text{if } 5 \mid n \text{ and } 3 \nmid n, \\ 3 & \text{if } 5 \mid n \text{ and } 3 \mid n. \end{cases} \] This function helps us select another function \( s_{f(n)}(n) \) which in turn determines the \( n \)th term of the Fizz Buzz sequence. Our goal now is to replace this piecewise formula with a single closed-form expression. To do so, we first define indicator functions \( I_m(n) \) as follows: \[ I_m(n) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } m \mid n, \\ 0 & \text{if } m \nmid n. \end{cases} \] The formula for \( f(n) \) can now be written as: \[ f(n) = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{if } I_5(n) = 0 \text{ and } I_3(n) = 0, \\ 1 & \text{if } I_5(n) = 0 \text{ and } I_3(n) = 1, \\ 2 & \text{if } I_5(n) = 1 \text{ and } I_3(n) = 0, \\ 3 & \text{if } I_5(n) = 1 \text{ and } I_3(n) = 1. \end{cases} \] Do you see a pattern? Here is the same function written as a table:

| \( I_5(n) \) | \( I_3(n) \) | \( f(n) \) |

|---|---|---|

| \( 0 \) | \( 0 \) | \( 0 \) |

| \( 0 \) | \( 1 \) | \( 1 \) |

| \( 1 \) | \( 0 \) | \( 2 \) |

| \( 1 \) | \( 1 \) | \( 3 \) |

Do you see it now? If we treat the values in the first two columns as binary digits and the values in the third column as decimal numbers, then in each row the first two columns give the binary representation of the number in the third column. For example, \( 3_{10} = 11_2 \) and indeed in the last row of the table, we see the bits \( 1 \) and \( 1 \) in the first two columns and the number \( 3 \) in the last column. In other words, writing the binary digits \( I_5(n) \) and \( I_3(n) \) side by side gives us the binary representation of \( f(n). \) Therefore \[ f(n) = 2 \, I_5(n) + I_3(n). \] We can now write a small program to demonstrate this formula:

for n in range(1, 101):

s = [n, 'Fizz', 'Buzz', 'FizzBuzz']

i = (n % 3 == 0) + 2 * (n % 5 == 0)

print(s[i])We can make it even shorter at the cost of some clarity:

for n in range(1, 101):

print([n, 'Fizz', 'Buzz', 'FizzBuzz'][(n % 3 == 0) + 2 * (n % 5 == 0)])What we have obtained so far is pretty good. While there is no universal definition of a closed-form expression, I think most people would agree that the indicator functions as defined above are simple enough to be permitted in a closed-form expression.

Complex Exponentials

In the previous section, we obtained the formula \[ f(n) = I_3(n) + 2 \, I_5(n) \] which we then used as an index to look up the text to be printed. We also argued that this is a pretty good closed-form expression already.

However, in the interest of making things more complicated, we must ask ourselves: What if we are not allowed to use the indicator functions? What if we must adhere to the commonly accepted meaning of a closed-form expression which allows only finite combinations of basic operations such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, integer exponents and roots with integer index as well as functions such as exponentials, logarithms and trigonometric functions. It turns out that the above formula can be rewritten using only addition, multiplication, division and the cosine function. Let us begin the translation. Consider the sum \[ S_m(n) = \sum_{k = 0}^{m - 1} e^{i 2 \pi k n / m}, \] where \( i \) is the imaginary unit and \( n \) and \( m \) are integers. This is a geometric series in the complex plane with ratio \( r = e^{i 2 \pi n / m}. \) If \( n \) is a multiple of \( m , \) then \( n = cm \) for some integer \( c \) and we get \[ r = e^{i 2 \pi n / m} = e^{i 2 \pi c} = 1. \] Therefore, when \( n \) is a multiple of \( m, \) we get \[ S_m(n) = \sum_{k = 0}^{m - 1} e^{i 2 \pi k n / m} = \sum_{k = 0}^{m - 1} 1^k = m. \] If \( n \) is not a multiple of \( m, \) then \( r \ne 1 \) and the geometric series becomes \[ S_m(n) = \frac{r^m - 1}{r - 1} = \frac{e^{i 2 \pi n} - 1}{e^{i 2 \pi n / m} - 1} = 0. \] Therefore, \[ S_m(n) = \begin{cases} m & \text{if } m \mid n, \\ 0 & \text{if } m \nmid n. \end{cases} \] Dividing both sides by \( m, \) we get \[ \frac{S_m(n)}{m} = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } m \mid n, \\ 0 & \text{if } m \nmid n. \end{cases} \] But the right-hand side is \( I_m(n). \) Therefore \[ I_m(n) = \frac{S_m(n)}{m} = \frac{1}{m} \sum_{k = 0}^{m - 1} e^{i 2 \pi k n / m}. \]

Cosines

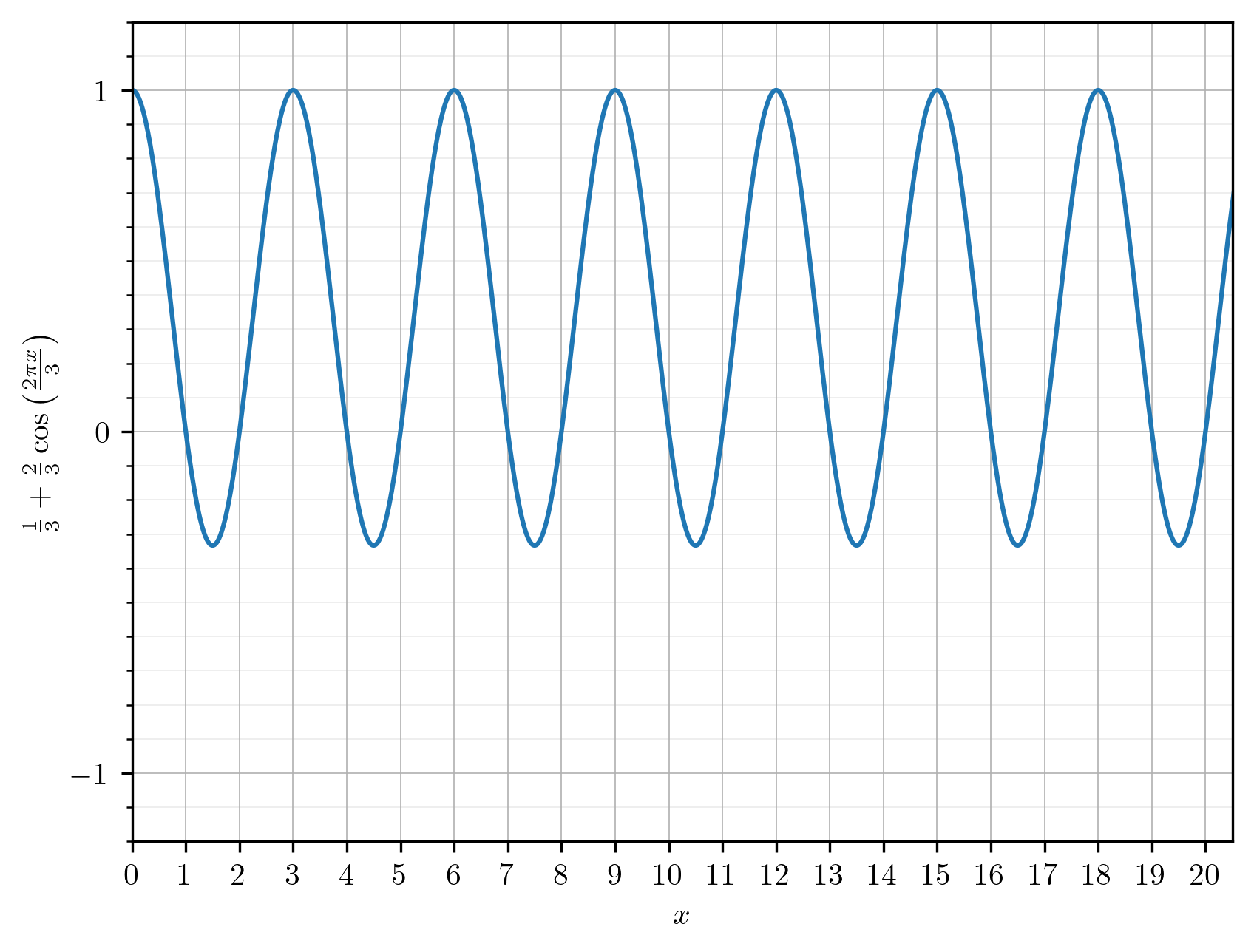

We begin with Euler's formula \[ e^{i x} = \cos x + i \sin x \] where \( x \) is a real number. From this formula, we get \[ e^{i x} + e^{-i x} = 2 \cos x. \] Therefore \begin{align*} I_3(n) &= \frac{1}{3} \sum_{k = 0}^2 e^{i 2 \pi k n / 3} \\ &= \frac{1}{3} \left( 1 + e^{i 2 \pi n / 3} + e^{i 4 \pi n / 3} \right) \\ &= \frac{1}{3} \left( 1 + e^{i 2 \pi n / 3} + e^{-i 2 \pi n / 3} \right) \\ &= \frac{1}{3} + \frac{2}{3} \cos \left( \frac{2 \pi n}{3} \right). \end{align*} The third equality above follows from the fact that \( e^{i 4 \pi n / 3} = e^{i 6 \pi n / 3} e^{-i 2 \pi n / 3} = e^{i 2 \pi n} e^{-i 2 \pi n/3} = e^{-i 2 \pi n / 3} \) when \( n \) is an integer.

The function above is defined for integer values of \( n \) but we can extend its formula to real \( x \) and plot it to observe its shape between integers. As expected, the function takes the value \( 1 \) whenever \( x \) is an integer multiple of \( 3 \) and \( 0 \) whenever \( x \) is an integer not divisible by \( 3. \)

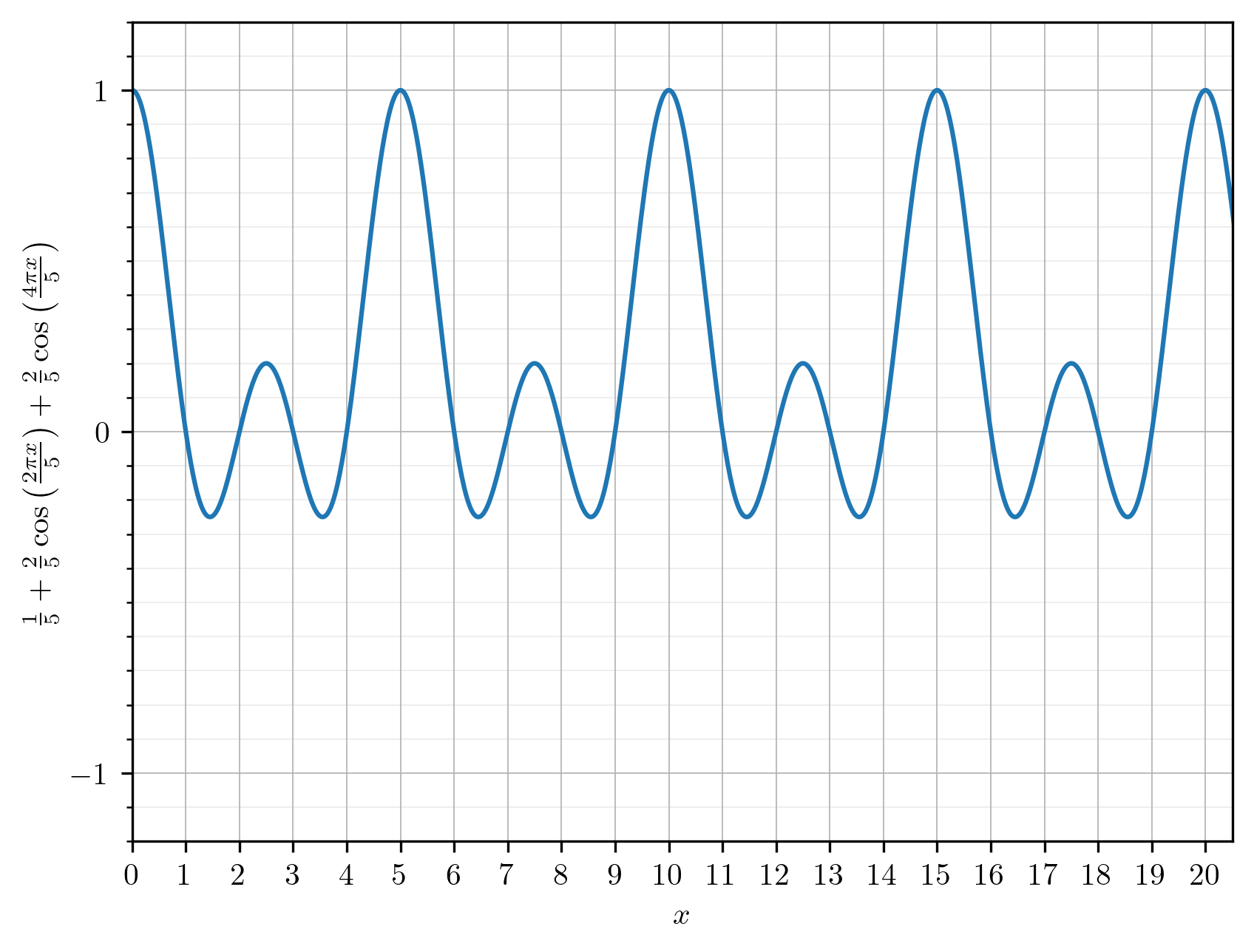

Similarly, \begin{align*} I_5(n) &= \frac{1}{5} \sum_{k = 0}^4 e^{i 2 \pi k n / 5} \\ &= \frac{1}{5} \left( 1 + e^{i 2 \pi n / 5} + e^{i 4 \pi n / 5} + e^{i 6 \pi n / 5} + e^{i 8 \pi n / 5} \right) \\ &= \frac{1}{5} \left( 1 + e^{i 2 \pi n / 5} + e^{i 4 \pi n / 5} + e^{-i 4 \pi n / 5} + e^{-i 2 \pi n / 5} \right) \\ &= \frac{1}{5} + \frac{2}{5} \cos \left( \frac{2 \pi n}{5} \right) + \frac{2}{5} \cos \left( \frac{4 \pi n}{5} \right). \end{align*} Extending this expression to real values of \( x \) allows us to plot its shape as well. Once again, the function takes the value \( 1 \) at integer multiples of \( 5 \) and \( 0 \) at integers not divisible by \( 5. \)

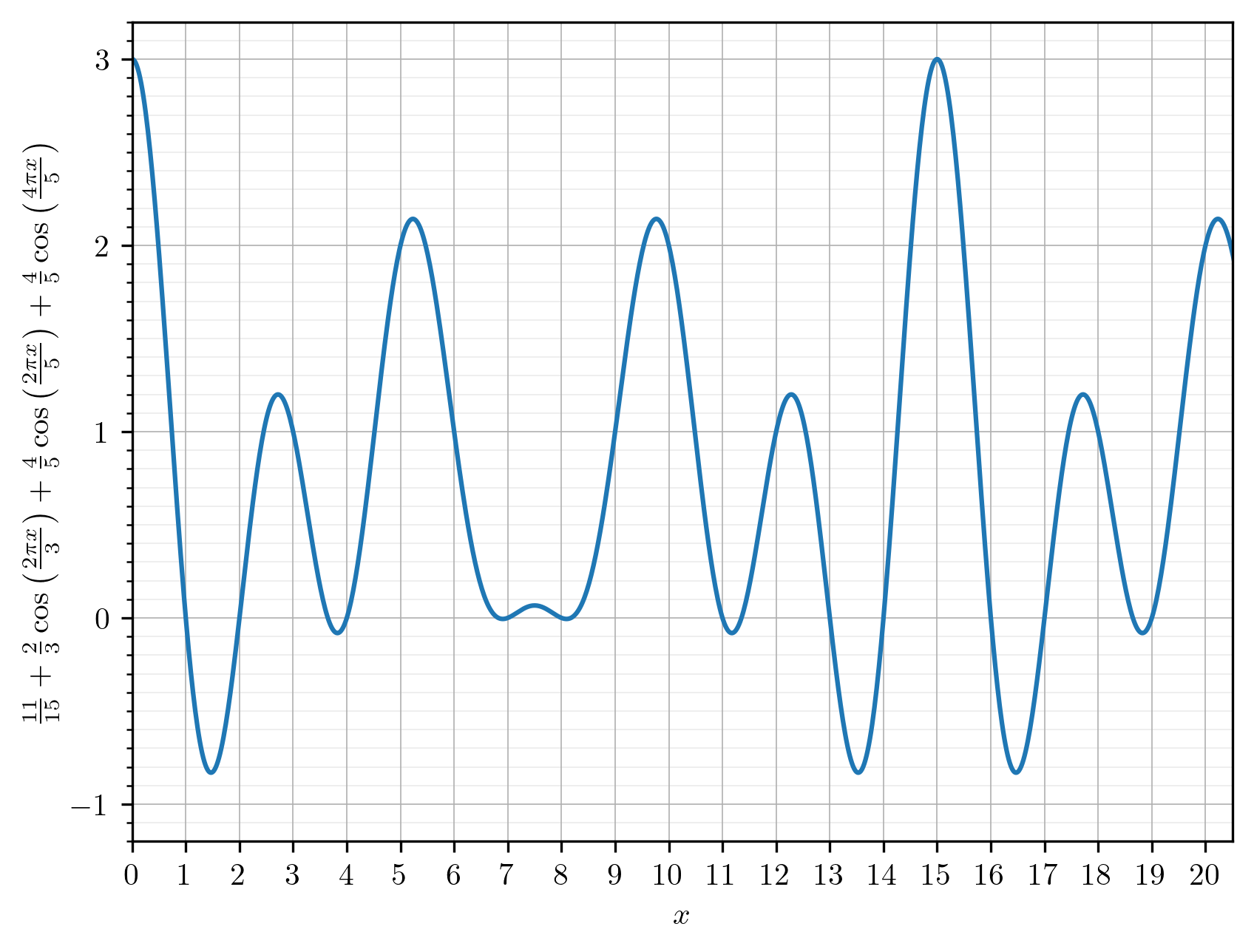

Recall that we expressed \( f(n) \) as \[ f(n) = I_3(n) + 2 \, I_5(n). \] Substituting these trigonometric expressions yields \[ f(n) = \frac{1}{3} + \frac{2}{3} \cos \left( \frac{2 \pi n}{3} \right) + 2 \cdot \left( \frac{1}{5} + \frac{2}{5} \cos \left( \frac{2 \pi n}{5} \right) + \frac{2}{5} \cos \left( \frac{4 \pi n}{5} \right) \right). \] A straightforward simplification gives \[ f(n) = \frac{11}{15} + \frac{2}{3} \cos \left( \frac{2 \pi n}{3} \right) + \frac{4}{5} \cos \left( \frac{2 \pi n}{5} \right) + \frac{4}{5} \cos \left( \frac{4 \pi n}{5} \right). \] We can extend this expression to real \( x \) and plot it as well. The resulting curve takes the values \( 0, 1, 2 \) and \( 3 \) at integer points, as desired.

Now we can write our Python program as follows:

from math import cos, pi

for n in range(1, 101):

s = [n, 'Fizz', 'Buzz', 'FizzBuzz']

i = round(11 / 15 + (2 / 3) * cos(2 * pi * n / 3)

+ (4 / 5) * cos(2 * pi * n / 5)

+ (4 / 5) * cos(4 * pi * n / 5))

print(s[i])Discrete Fourier Transform

The keen-eyed might notice that the expression we obtained for \( f(n) \) is a discrete Fourier series. This is not surprising, since the output of a Fizz Buzz program depends only on \( n \bmod 15. \) Any function on a finite cyclic group can be written exactly as a finite Fourier expansion. In this section, we obtain \( f(n) \) using the discrete Fourier transform. It is worth mentioning that the calculations presented here are quite tedious to do by hand. Nevertheless, this section offers a glimpse of how such calculations are performed. By the end, we will arrive at exactly the same \( f(n) \) as before. There is nothing new to discover here. We simply obtain the same result by a more direct but more laborious method. If this doesn't sound interesting, you may safely skip the subsections that follow.

One Period of Fizz Buzz

We know that \( f(n) \) is a periodic function with period \( 15. \) To apply the discrete Fourier transform, we look at one complete period of the function using the values \( n = 0, 1, \dots, 14. \) Over this period, we have: \begin{array}{c|ccccccccccccccc} n & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 6 & 7 & 8 & 9 & 10 & 11 & 12 & 13 & 14 \\ \hline f(n) & 3 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 2 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 2 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \end{array} The discrete Fourier series of \( f(n) \) is \[ f(n) = \sum_{k = 0}^{14} c_k \, e^{i 2 \pi k n / 15} \] where the Fourier coefficients \( c_k \) are given by the discrete Fourier transform \[ c_k = \frac{1}{15} \sum_{n = 0}^{14} f(n) e^{-i 2 \pi k n / 15}. \] for \( k = 0, 1, \dots, 14. \) The formula for \( c_k \) is called the discrete Fourier transform (DFT). The formula for \( f(n) \) is called the inverse discrete Fourier transform (IDFT).

Fourier Coefficients

Let \( \omega = e^{-i 2 \pi / 15}. \) Then using the values of \( f(n) \) from the table above, the DFT becomes: \[ c_k = \frac{3 + \omega^{3k} + 2 \omega^{5k} + \omega^{6k} + \omega^{9k} + 2 \omega^{10k} + \omega^{12k}}{15}. \] Substituting \( k = 0, 1, 2, \dots, 14 \) into the above equation gives us the following Fourier coefficients: \begin{align*} c_{0} &= \frac{11}{15}, \\ c_{3} &= c_{6} = c_{9} = c_{12} = \frac{2}{5}, \\ c_{5} &= c_{10} = \frac{1}{3}, \\ c_{1} &= c_{2} = c_{4} = c_{7} = c_{8} = c_{11} = c_{13} = c_{14} = 0. \end{align*} Calculating these Fourier coefficients by hand can be rather tedious. In practice they are almost always calculated using numerical software, computer algebra systems or even simple code such as the example here: fizz-buzz-fourier.py.

Inverse Transform

Once the coefficients are known, we can substitute them into the inverse transform introduced earlier to obtain \begin{align*} f(n) &= \sum_{k = 0}^{14} c_k \, e^{i 2 \pi k n / 15} \\[1.5em] &= \frac{11}{15} + \frac{2}{5} \left( e^{i 2 \pi \cdot 3n / 15} + e^{i 2 \pi \cdot 6n / 15} + e^{i 2 \pi \cdot 9n / 15} + e^{i 2 \pi \cdot 12n / 15} \right) \\ & \phantom{=\frac{11}{15}} + \frac{1}{3} \left( e^{i 2 \pi \cdot 5n / 15} + e^{i 2 \pi \cdot 10n / 15} \right) \\[1em] &= \frac{11}{15} + \frac{2}{5} \left( e^{i 2 \pi \cdot 3n / 15} + e^{i 2 \pi \cdot 6n / 15} + e^{-i 2 \pi \cdot 6n / 15} + e^{-i 2 \pi \cdot 3n / 15} \right) \\ & \phantom{=\frac{11}{15}} + \frac{1}{3} \left( e^{i 2 \pi \cdot 5n / 15} + e^{-i 2 \pi \cdot 5n / 15} \right) \\[1em] &= \frac{11}{15} + \frac{2}{5} \left( 2 \cos \left( \frac{2 \pi n}{5} \right) + 2 \cos \left( \frac{4 \pi n}{5} \right) \right) \\ & \phantom{=\frac{11}{15}} + \frac{1}{3} \left( 2 \cos \left( \frac{2 \pi n}{3} \right) \right) \\[1em] &= \frac{11}{15} + \frac{4}{5} \cos \left( \frac{2 \pi n}{5} \right) + \frac{4}{5} \cos \left( \frac{4 \pi n}{5} \right) + \frac{2}{3} \cos \left( \frac{2 \pi n}{3} \right). \end{align*} This is exactly the same expression for \( f(n) \) we obtained in the previous section. We see that the Fizz Buzz index function \( f(n) \) can be expressed precisely using the machinery of Fourier analysis.

Conclusion

To summarise, we have defined the Fizz Buzz sequence as \[ (s_{f(n)}(n))_{n = 1}^{\infty} \] where \[ f(n) = \frac{11}{15} + \frac{2}{3} \cos \left( \frac{2 \pi n}{3} \right) + \frac{4}{5} \cos \left( \frac{2 \pi n}{5} \right) + \frac{4}{5} \cos \left( \frac{4 \pi n}{5} \right). \] and \( s_0(n) = n, \) \( s_1(n) = \mathtt{Fizz}, \) \( s_2(n) = \mathtt{Buzz} \) and \( s_3(n) = \mathtt{FizzBuzz}. \) A Python program to print the Fizz Buzz sequence based on this definition was presented earlier. That program can be written more succinctly as follows:

from math import cos, pi

for n in range(1, 101):

print([n, 'Fizz', 'Buzz', 'FizzBuzz'][round(11 / 15 + (2 / 3) * cos(2 * pi * n / 3) + (4 / 5) * (cos(2 * pi * n / 5) + cos(4 * pi * n / 5)))])We can also wrap this up nicely in a shell one-liner, in case you want to share it with your friends and family and surprise them:

python3 -c 'from math import cos, pi; [print([n, "Fizz", "Buzz", "FizzBuzz"][round(11/15 + (2/3) * cos(2*pi*n/3) + (4/5) * (cos(2*pi*n/5) + cos(4*pi*n/5)))]) for n in range(1, 101)]'We have taken a simple counting game and turned it into a trigonometric construction consisting of a discrete Fourier series with three cosine terms and four coefficients. None of this makes Fizz Buzz any easier. Quite the contrary. But it does show that every \( \mathtt{Fizz} \) and \( \mathtt{Buzz} \) now owes its existence to a particular set of Fourier coefficients. We began with the modest goal of making this simple problem more complicated. I think it is safe to say that we did not fall short.